|

INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF WALK

|

Postcard of Sutter’s Fort and

St. Francis of Assisi Church [SPL/SR] |

Standing in front of St. Francis of Assisi Church, we look up at a beautiful mission façade,

with red tile roofs and walls painted in delightfully complimentary colors. This has not always been

the case; before the 1983 restoration the church was painted a dark, foreboding Folsom Prison

gray.

|

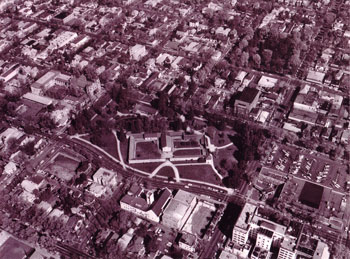

Aerial view of Sutter’s Fort and

St. Francis of Assisi Church [SAMCC] |

Walking around to the 26th and K Street corner of the church, we see that the cornerstone

was laid in 1908 – thus the centennial celebration in 2008. We are also standing on the same

ground where the original wooden church was dedicated in 1895.

|

|

Print of St. Francis Church,

Dennis Rietz, S.F.O., 1995 |

The elevation at the curb in front of the cornerstone is 19.76 feet above sea level –

interesting to contemplate with predications that global warming may raise sea levels twenty feet

or more. The global positioning coordinates at the bottom step in front of the church are:

38 degrees 34.396 Minutes N

121 degrees 28.342.minutes W

Cartagena is very close to the Greenwich Meridian, 0 degrees – or Zulu time in

airline/military parlance. (Sacramento is seven hours behind Greenwich Mean Time). Continuing

eastward through Palermo, Sicily; Athens, Greece; Izmir, Turkey; Ashgabat, Turkmenistan;

Baotou, China; Seoul, Korea; Niigata, Japan; and across the North Pacific, crossing the

International Dateline (the 180th meridian), where we lose a day, and back to Sacramento, or more

precisely the front steps of St. Francis of Assisi Church. |

|

World Map,

38th parallel [CSUS] |

This brief “walk” around the front of the church helps us to better understand our parish

within larger historical and geographical contexts.

|

Sutter's Fort ruins, c. 1889,

with horse-drawn streetcar [SAMCC] |

Across the street stands a restored Sutter’s Fort, a destination for overland travelers in

the 1840s and a source of respite for the Donner Party after they were rescued by John Sutter

and others in early 1847. Sold by Sutter’s son, August Jr., in 1849 for $40,000 to pay off some of his

father’s debts, the fort fell into ruin but was restored between 1891 and 1893 through the efforts of the

Native Sons of the Golden West and others. In 1908, the Sacramento Chamber of Commerce,

which had formed in 1895, agreed to help fund a new St. Francis Church when the Franciscans

agreed to a mission façade for the church, the goal of local boosters being to create a

neighborhood tourist attraction.

Turning to the pond behind the fort and the State Indian Museum, we can extend our

imaginative gaze further back in time to “see” the Native American Miwok people who would in

the summer months make their home on the banks of this branch of the American River. In the

spring, they would move down into the valley from their winter homes, as the waters of the

American and Sacramento rivers receded – prior to Euro-American settlement, river waters

flooded for miles across the valley. The Miwok people would spend summer and early fall

gathering the fish, fowl, wildlife, roots, herbs, and berries of the valley until fall rains told them to

move to higher ground for the winter.

|

THE INTERNATIONAL FUR TRADE

This cycle of life endured throughout the region for thousands of years until Hudson’s Bay

Company trappers brought European diseases into the valley in the early 1830s. Headquartered

at York Factory on the southern shore of Hudson’s Bay, the Hudson’s Bay Company was, during the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the largest transglobal enterprise on the North American

continent. Established in 1670, the company charter granted it exclusive trading rights in Prince

Rupert’s Land – Hudson Bay’s 1.5 million-square-mile drainage basin.

|

Map of Prince Rupert’s Land

[Encarta] |

Over the decades, Hudson’s Bay Company trappers harvested luxury fur-bearing animals

to extinction. Company policy was to create a “fur desert” – taking all for themselves, while

leaving nothing for others. In this process, the company constantly drove westward and southward. In

extending their quest for luxury pelts – beaver, marten, otter, etc. – across Canada to the Pacific

Coast, the Hudson’s Bay Company in the early years of the nineteenth century came into

competition with both Russian and American fur-trading enterprises.

|

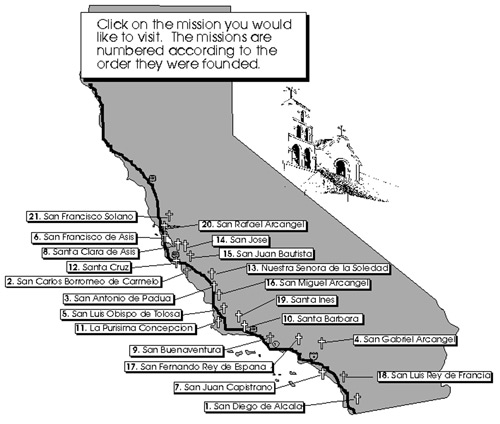

| Mission San Diego |

A region of both commercial profit and geopolitical advantage, the Pacific Coast was

contested during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries among the Hudson’s Bay Company,

Spain, Russia, Great Britain, Mexico, and the United States – each competing for its resources and

strategic location. Amid this turmoil, Spanish religious presence in Alta California began

with the founding of Mission San Diego by Fr. Junipero Serra in 1769. Although the Franciscan

Friars and their neophytes were less directly engaged in the luxury fur trade than others, European

presence and fur-trading predations invariably resulted in devastating consequences for Native peoples.

|

Map of the Twenty-One Franciscan Missions

[missions.bgmm.com] |

|

| Twenty-One Franciscan Missions |

Founded in 1799, the Russian American Company’s quest for sea otter pelts had a

disastrous effect on Native peoples, beginning with the Aleutian Indians whom they murdered and

enslaved. Founding Fort Sitka in Alaska in 1804, the Russian American Company sent Aleut sea

otter-hunting expeditions further and further south along the coast as their forays depleted

existing populations. Between 1803 and 1805, more than 17,000 sea otter pelts were taken in

California waters.

|

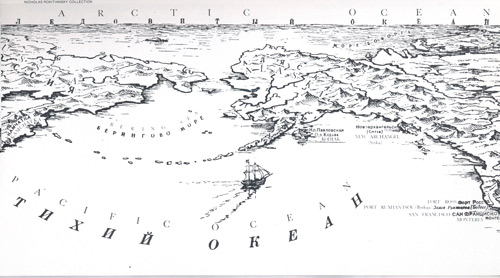

Russian American Map, Kamchatka to Fort Ross

[Fort Ross Archives] |

|

| Sea Otters |

At times, American ship captains worked in concert with the Russian American Company

– a joint venture in which the Russians supplied the labor of Native Alaskans and their seal-skin

kayaks, while American merchants supplied the ships. Under this arrangement, three Boston-owned ships – the Albatross, the Isabella, and the O’Cain — brought in the highest recorded catch

of otter – 9,356 pelts in the 1810-1811 season. At that time, there was a tremendous demand for

otter skins among the Chinese upper classes, who might pay as much as a company laborer's annual

earnings for one pelt. |

COMPETING INTERNATIONAL INTERESTS

|

Map of Fort Clatsop/Astoria

[Encarta] |

With such wealth at stake fromsea otter pelts alone, it is no wonder that the Pacific Coast

region was sought after as a prize. In 1778, Great Britain’s Captain James Cook explored and mapped

the Pacific Coast from California to the Bering Strait. In 1792 a member of Captain George

Vancouver’s expedition sailed up the Columbia River as far as the Columbia Gorge. Vancouver's

and Cook’s explorations strengthened England’s claim to the region initiated by Sir Francis

Drake’s landing on the Pacific Coast in 1579. In 1824 the Hudson’s Bay Company established

Fort Vancouver as a fur trading post. From there they made their first foray into California in 1829.

President Thomas Jefferson’s 1805-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition was in large part

an effort to strengthen American claims to the Pacific Coast region. Lewis and Clark’s “Voyage of

Discovery” wintered at Fort Clatsop at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1805-1806, returning east

to St. Louis in the spring of 1806.

In 1811, John Jacob Astor 1763-1848) established Astoria as a site for his Pacific Fur

Company post. The son of a butcher, born in Waldorf, Germany, in 1763, John Jacob arrived in

New York City in 1784 via London, where he had worked with his brother selling musical instruments.

Within decades he had become one of the young republic’s foremost fur traders – securing furs in Canada,

the Great Lakes region, and the Pacific Northwest, and trading on the international market with countries as distant

as China and England.

Note: Fort Vancouver, Washington is about 100 miles up the Columbia River

from Astoria, opposite Portland, Oregon.

Astoria, the first permanent American settlement in the Pacific Northwest, strengthened

the United States' claim to the region. But sensing a shift in the fur trade, Astor sold the site to the

Hudson’s Bay Company in 1813. With the wealth he had made in the fur trade, he invested in

New York City land – becoming America’s first millionaire, and according to Forbes, the fourth

wealthiest person in American history as of this writing.

The Russian American Company continued to move south – and west. In 1812 they

established Fort Ross, within 90 miles of Yerba Buena (San Francisco). In 1815 they briefly

established Fort Elizabeth at Waimea, Kauai, in the Hawaiian Islands.

In 1819 the United States strengthened its claims to the Pacific Northwest Coast with the

Adams-Onis Treaty, in which Spain agreed to setting the 42nd parallel (which would become California’s

northern border) as the northern limit of its claims.

|

Sketch of Mission San Francisco de Solano

and Sonoma Presidio |

Between 1821 and 1822, Mexico won its independence from Spain – further

exacerbating conflicts on the Pacific Coast, as the young Mexican Republic was even less able than

Spain to defend its sovereignty and regulate trade in Alta California. In an effort to strengthen

their presence on their northern frontier, the Mexican government established Mission San

Francisco de Solano in 1823 – some 45 miles north of Yerba Buena (San Francisco). In a further

effort to reinforce their control, they established the Sonoma Presidio Barracks under the

command of General Mariano Vallejo in 1836.

|

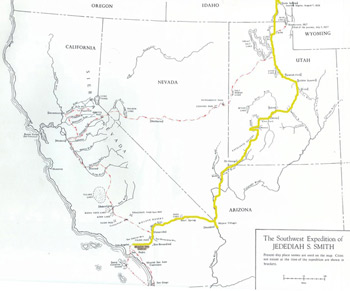

| Map of Jedediah Smith, 1826 [CSUS] |

In late November 1826, owever, Jedediah Smith and his fur-trapping party arrived at

Mission San Gabriel (about five miles southeast of present-day Pasadena). Smith’s party had left

the second annual fur traders rendezvous in Soda Springs, Idaho, in late August and traveled via

the Mojave Villages (near present-day Needles, California) to Mission San Gabriel – a journey of nearly

1,000 miles.

Jedediah Smith and his party were the first Americans to arrive overland from the United

States — they would not be the last. Officials of the young Mexican government were well aware

of American incursions and designs, and they suspected Smith of being a spy. He was called

before Governor Echeandia at San Diego, some 120 miles to the south, where after days of

questioning and the support of American ship captains, he was released with the promise that he

would leave Mexican territory by retracing his route to the east.

|

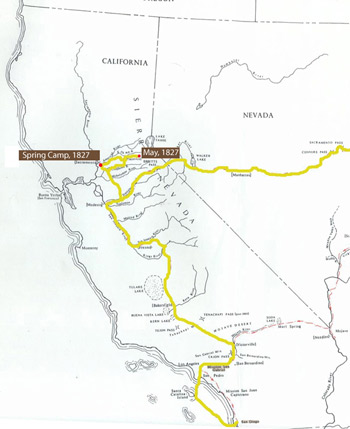

| Map of Jedediah Smith in California [CSUS] |

Instead, Smith wintered at ission San Gabriel and, in the spring of 1827, set out

north through the San Joaquin Valley, striking the American River in the vicinity of today’s

Rosemont and camping a mile or so east of its mouth in what today would be Sutter Discovery

Park (formerly the city's landfill). In early May 1827, he attempted to cross the Sierra via the South

Fork of the American River. According to historians’ estimates from Smith’s journals, he found his

way blocked by five to seven feet of snow at what would today be Pacific, California, some 60 miles east of

Sacramento at about 3,400 feet elevation. Echo Summit, at 7,377 feet elevation, lay some 4,000 feet and

30 miles above him.

Returning to the valley, Smith followed the Stanislaus River eastward, crossing the Sierra at

Ebbetts Pass in late May. Thus he and his small party were the first Euro-Americans to traverse

the Sierra Nevada. In late 1827, he returned to California by way of the Mojave with a larger fur-trapping party. |

THE REPUBLIC OF MEXICO AND JOHN A. SUTTER

In the 1830s Mexican officials took further steps to govern Alta California. California

Mission Friars were trading with increasing numbers of New England merchant ships whose

captains were happy to accept all the cattle hides, tallow, and furs they could secure. Committed

as they were to a scientific, rational anticlerical liberalism, many officials of the Mexican Republic

viewed the missions as large-scale smuggling operations worked by Native “slave” labor. Thus, in

1833, the Mexican government passed a law secularizing all mission lands and property; this law was

implemented between 1834 and 1836.

|

Book Cover - John Sutter:

A Life on the North American Frontier

by Albert L. Hurtado (2006) |

To further strengthen Mexican control over nterior Alta California, in 1839 the governor at

Monterey, Juan Bautista Alvarado, granted John A. Sutter (1803-1880) the right to settle in the

Sacramento Valley. As assessed by his most recent biographer, Albert Hurtado, John Sutter was

a man who felt excluded, denied his proper place in the world, and was thus driven by tremendous

striving energy. Born to a Swiss father and a German mother in Baden, Germany, Sutter was

neither fully German nor fully Swiss. He excelled in school, but authorities held that his official

status was that of his grandfather, a peasant farmer.

Sutter sought success and respectability in business – but this, too, eluded him. In 1826,

one day before the birth of his son, John Augustus Sutter Jr., he married Annette D’beld, a

woman far above his social status. The couple had four more children at 18-month intervals.

Investing his mother-in-law’s money in a dry goods business, Sutter was by January

1834 facing debtor’s prison. Thus he chose to abandon his debts, his wife, and his children and

flee to America. Sutter’s destination was a German colony near St. Louis, which he reached late in

1834, via Le Havre, France; New York City; and Cincinnati, Ohio. There he entered into a

business venture, trading goods to Santa Fe, Mexico. His first venture was modestly successful,

but a second trip proved to be a financial disaster. Following other business failures and mounting

debts, Sutter next set his sights on California.

|

Map of Sutter's journey

from Burgdorf, Switzerland, to St. Louis [CSUS].

His two round-trip ventures to Santa Fe

added more than 4,000 miles to his travels. |

|

Map of Sutter's journey

from Westport, Kansas, to Fort Vancouver, Washington [CSUS] |

Sutter’s 1838 westward trek reveals much, not only about his resolve, but also about the

extent of Hudson’s Bay Company operations. Sutter left Westport, Kansas, on April 1, 1838 – one

day before a scheduled court appearance to answer a creditor’s charges. On June 23, in the

company of an American fur trading party, he arrived at the confluence of the Popo Agie and

Wind Rivers (Riverton, Wyoming), the site of the 1838 fur traders' rendezvous – a distance of more

than 900 miles.

On July 12, 1838, Sutter left the Popo Agie in the company of a Hudson’s Bay Company

party led by Francis Ermantinger, a Canadian of Swiss origin. In route, they stopped at Hudson’s

Bay Company trading posts -- Fort Hall (Pocatello, Idaho), Fort Boise (Idaho), and Fort Walla

Walla (Washington). Sutter arrived at Fort Vancouver (Washington) in late October, having

traveled more than 1,000 miles through Hudson’s Bay Company territory.

|

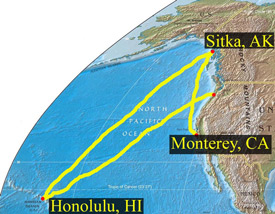

Map of Sutter's journey

from Fort Vancouver to Honolulu

to Sitka and eventually Monterey [CSUS] |

From Fort Vancouver, Sutter boarded theHudson’s Bay Company ship Columbia, which

took him to another Hudson’s Bay Company post in Honolulu, Hawaii. He wintered in Honolulu,

sailing to the Russian American Fur Company post at Sitka, Alaska, in April 1839 and from there

to Monterey via San Francisco, where he arrived in early July 1839.

Sutter seemed to make up the story of his life and embellish it the more as he traveled

further west. He was charming; more successful men loaned him money and wrote letters of

recommendation for him. By the time he arrived in Hawaii, he had elevated himself to the status of

a former officer in the Swiss Guard – thus his self-acquired credentials opened the way for him to

advise the Hawaiian king, Kamehameha III, on military matters. Moreover, Sutter acquired both

letters of recommendation and extensive lines of credit from Honolulu merchants William French,

William Heath Davis, Eliab Grimes, and his nephew Hiram Grimes.

|

Portrait of John A. Sutter

by William S. Jewett (1853) [CSL] |

As we know, Sutter was an aspiring Swiss-German entrepreneur who had fled failed

business ventures in his native country, in Santa Fe (Mexico), and in Kansas. Albert Hurtado

notes: “He was one of the poorest businessmen in the history of capitalism.” He would also go

bankrupt in Sacramento. Nevertheless, Sutter was a visionary, who saw in the Sacramento Valley his “New

Helvetia” – his own many-splendored barony.

Sutter’s path to empire was cleared for him by disease. In 1833 a Hudson’s Bay

Company brigade under the command of John Work moved south from Fort Vancouver into the

Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys. With them they brought European diseases — principally

malaria — for which Native Americans had no immunity. Thus was repeated a pattern of “virgin

soil” devastation that occurred on frontier after frontier in the Western Hemisphere – earlier in

Alta California with the arrival of the Franciscans; in Virginia, New England, the St. Lawrence

River Valley; in Central and South America; and most completely in the Caribbean Islands following

Columbus’s voyages. Ethnographers estimate that disease epidemics of the 1830s killed 75

percent of the Native population in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys, leaving behind a

disoriented and dispirited remnant that offered little resistance when Sutter’s party disembarked

on the south shore of the American River in August 1839.

By August 1839, John Sutter had been "on the road" for five years and three months — since his

departure from Burgdorf in May 1834. He had traveled more than 18,000 miles – across the Atlantic, across the

continent, on to Hawaii, and north to Russian Alaska. He had visited many of the major Western forts and

trading posts, where he had won the respect of leaders and men of substance, not least of all the king of

Hawaii. Encamped on a knoll about a mile south of the American River, Sutter seemed to be on the

threshold of realizing his dreams.

|

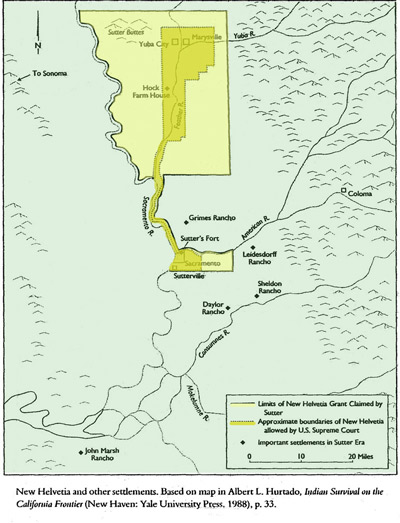

Map of Sutter’s Claims and Final Grant

(Hurtado, Sutter, p. 64) |

For a time he was successful. By 1841, Sutter had secured a land grant of eleven leagues

(47,827 acres) from Governor Alvarado in Monterey, enserfed the Native American Miwok to

build his fort, weave blankets, tend his herds of cattle and horses, plant and harvest his wheat fields, work in his

orchards, distilleries, tanneries, plus his other enterprises, as well as staff his army. From the fort, Sutter's

lines of interests and endeavors extended out into the South Pacific, Central America, Europe, Alaska, Russia,

Asia, and midwestern and eastern cities of the United States.

By the 1830s the Russians realized that the sea otter population had been so ravaged

that commercial operations were no longer profitable. Thus, in 1841 they sold Fort Ross, and all

its furnishings, to John Sutter for $30,000.

|

MANIFEST DESTINY, AMERICAN CONQUEST

American Manifest Destiny would not be denied. In 1846, the United States precipitated a

war with Mexico and, with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, secured possession of 525,000

square miles – all of the states of California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as parts of Colorado, New

Mexico, Arizona, and Wyoming.

|

Map of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,

1848 [Encarta] |

|

Book Cover, J. S. Holliday,

The World Rushed In (1989) |

When Sutter arrived at the fort in 1839, he had established a "multiethnic" community, bringing with

him ten Kanakas (eight Hawaiian men and two women), three European males, and a Native

American slave boy. By the early 1840s there were “thirty white men” at the fort — Germans,

Swiss, Canadians, French, and English, as well as a number of Americans, including John

Bidwell, who had led the first wagon train overland to California in 1841 and who served as Sutter’s

assistant and secretary. But with the discovery of gold in January 1848 on the South Fork of the

American River at Coloma, in the words of historian, J. S. Holliday, “the world rushed in.”

Sutter’s Fort became a staging area for thousands of gold seekers. In contrast to

conventional wisdom, the Gold Rush did not destroy Sutter, who was already essentially bankrupt since

“purchasing” Fort Ross. In December 1841, Sutter had signed promissory notes with the Russians

for $30,000, for which he received all the buildings at Fort Ross, cattle, stores, implements,

cannon, and the schooner Constantine, which he renamed the Sacramento. Given the extent of

his enterprises and the degree of his already substantial debt, there was little likelihood that Sutter

would be able to settle his obligations to the Russians under any terms.

By 1849, however, John Augustus Sutter Jr. and Augustus's attorney, Peter H. Burnett, were

able to pay off ALL of Sutter’s extensive debts through the sale of Sacramento city lots. Sutter’s

son, the child who had been born one day after their parents wed on October 24, 1826, arrived

unbidden in Sacramento in August 1848. His father, who saw in his son a way to escape his

crushing debts, welcomed him. In mid-October, Sutter signed over all of his property (and debts)

to young Augustus. In December 1848, Augustus hired Captain William Warner to plat out the City of

Sacramento; and in the same month, he signed a contract with Peter H. Burnett to sell city lots and

liquidate Sutter’s debts — which Burnett did.

At this juncture in his life, with thousands of acres of land claims (though some were quite

dubious), Sutter, as Augustus said, had the potential to be “one of the richest men in California."

If only Sutter had remained out of the picture and allowed Augustus and Burnett to

continue their work! But the elder Sutter quarreled with his son and “retired” to his rancho at Hock

Farm on the Feather River south of Marysville. Soon he took back control of his affairs from

Augustus, fired Burnett, and reverted to his old business practices, bringing himself into further legal

complications and conflicts and, once again, ever-mounting debt.

|

THE CITY OF SACRAMENTO

|

| Lithograph of the City of Sacramento 1855 [SAMCC] |

Captain Warner’s “Old City” grid ran from Front/1st Street/Embarcadero at the Sacramento

River east to 31st Street, and from A Street south to W Street. Much of the land north of the

business district and south of R Street, however, was too swampy to survey or subdivide.

|

| Map of the Sacramento River Watershed [SRCSD] |

The grid system of urban development was first used in North America in Philadelphia in

1683. Like Sacramento, Philadelphia was sited between two rivers, the Delaware and the

Schuylkill, but the 27,000-square-mile Sacramento River Watershed is one of the largest and

most volatile in the lower forty-eight states. As Native Americans and John Sutter understood,

flooding was inevitable. Sutter himself was surrounded by flood waters on his knoll during the

winter of 1839-1840.

|

Book Cover: Kelley, R.,

Battling the Inland Sea

(1989 hardcover edition) |

The first flood in Sacramento city history occurredin January 1850, with a second in

March. The first levees were then constructed . . . three feet high. Thus began what historian

Robert Kelley has called the battle against “the inland sea,” a battle that continues today and will

continue as long as there is development in the Sacramento Valley.

Sacramento experienced more floods in 1852 and 1853, but the most devastating floods

occurred in the winter of 1861-1862, halting construction on the State Capitol building. As a result

of these floods, streets in the business district were raised 12 to 15 feet, with soil excavated to

straighten out the American River and move its mouth about a mile or so to the north. This work,

done with horse-drawn scrapers, mules, and hand carts, continued throughout most of the 1860s.

|

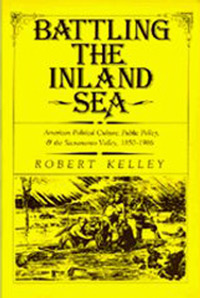

| Fire Damage to the City of Sacramento, 1852 [SAMCC] |

With structures built of wood and canvas, Sacramento in its early years was also subject

to devastating fires. The first fire occurred in 1852, and a fire in 1854 destroyed seven-eighths of

the business district. Thereafter, Sacramentans built their structures with the more fire-resistant brick. |

AMERICAN DOMINANCE

|

California State Seal

[California State Archives] |

Americans were quick to establish their own forms of government in California. In 1849 the City of

Sacramento was organized, and the California Constitutional Convention was held in Monterey.

Sutter was a delegate to the convention that drafted a constitution modeled on the U.S. Constitution.

The California Constitution guaranteed Spanish/Mexican land grants and citizenship

to all Euro-American residents (but not to Native Americans). The Constitution also made California

a joint-property state, reflecting the goal of Spanish Catholic culture to protect the family's rights before

the individual rights of male property holders; and the Constitution was printed in two languages – English

and Spanish.

|

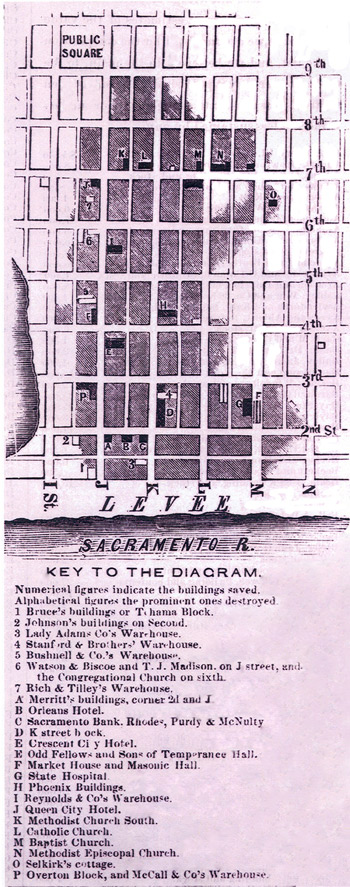

| Map of the Mt. Diablo Meridian and Baseline [MDSHS] |

Americans also established their own systems of taxation, courts, and land tenure. In July

1851, a United States survey party established the Mt. Diablo baseline and meridian. Thereafter,

title to most land in Northern California and Nevada would be determined by the United States

Public Land Survey System, originated by Congress with Thomas Jefferson’s Land Ordinance of

1785. The combination of U.S. taxes, court procedures, land surveys, and title searches

effectively stripped native-born, Spanish-speaking Californians (Californios) of their wealth, land

holdings, and social and economic standing within a few generations.

With the gold rush came more disease. In 1849 a hospital was established at Sutter’s

Fort to fight a malaria epidemic. In October 1850, cholera arrived aboard the river steamer, New

World, also carrying the news that California had been admitted into the Union as the 31st state on

September 9, 1850. Thus, disease, floods, and fires marked the early history of Sacramento, but

amidst the drama of the Gold Rush and natural calamities, other forces were at work establishing

political, civic, and cultural institutions.

|

| State Capitol Construction, c. 1873 [SPL/SR] |

In 1854, Sacramento was designated the capital of California, thus securing the city’s

prominence in state history, to the great relief of city fathers. For some four years the state's

“capitol on wheels” had convened at San Jose, Sacramento, Vallejo, and Benicia, before the

legislature voted in February 1854 to make Sacramento its permanent home. Construction on

the State Capitol building begun in 1860 was completed in 1874. |

SACRAMENTO: EARLY RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES

In addition to establishing political institutions, Sacramentans from the earliest years attended to their

religious needs. In late 1849, the first Episcopal service was held in Sacramento, the

Congregational Church of Christ formed, the first Methodist service took place at 3rd and L

under a large oak tree, and the Hebrew Benevolent Society and cemetery were organized. St.

Andrews African Methodist Episcopal Church came together in 1850.

|

Fr. Peter A. Anderson

[Sacramento Diocese] |

Catholic religious life began on August 11, 1850, when Fr. Peter A. Anderson

celebrated the first Mass at a private home on 5th and L; later that day, Fr. Anderson officiated

at Sacramento’s first Catholic baptism — for Thomas Taylor, who had been born in May 1850 aboard a ship off the coast of Peru.

Fr. Anderson died in the cholera epidemic that November. But Bishop Joseph

Sadoc Alemany visited the city in December, and Peter Burnett donated land for St. Rose of

Lima Church at 7th and K Streets. St. Rose served as Sacramento’s only Catholic Church until 1887.

|

| St. Rose of Lima, early 1860s [SAMCC] |

The first two St. Rose of Lima churches, built of wood, were destroyed in the fires of 1852

and 1854. In October 1854, a new and larger brick church was begun under the direction of Fr.

John Quinn. The first Mass was celebrated in the basement on Christmas 1855. The new St. Rose

was dedicated in 1856 and completed in 1861. During the 1860s, the streets of Sacramento

were raised; and thereafter, parishioners had to descend a short staircase to enter St. Rose. In

addition, the floods of 1861-1862 damaged the foundations of the church, so that over the years it

became an increasingly unstable and unsafe structure.

|

| St. Rose of Lima, after 1860s [SAMCC] |

By 1857, the first nuns - the Sisters of Mercy — arrived in the city to see to the education of

young Catholics. Initially they used two rooms in the back of St. Rose for a school.

Ultimately they bought property at 8th and G, where they opened a school for girls, St. Joseph’s

Academy and Orphanage, in 1861.

|

Postcard with Carriage,

Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament [SPL/SR] |

The Diocese of Sacramento was stablished in 1886, with Patrick Manogue as the first

Bishop. He quickly arranged financing and construction at 11th and K Streets of the Cathedral of the Blessed

Sacrament, which was dedicated in 1889. Thus, by 1890 Sacramento

possessed two buildings marking the city’s secular and sacred prominence – the State Capitol

at 11th and L and the Cathedral at 11th and K.

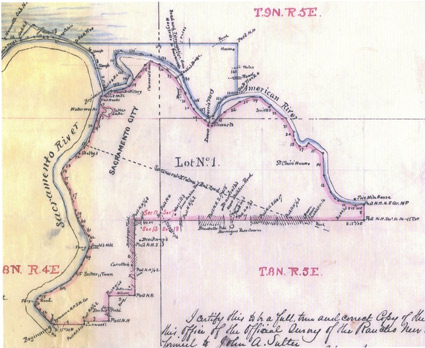

St. Francis of Assisi, the second parish in the city, was organized in 1894 by

German Franciscans. Documents in the Santa Barbara Mission Archives note that the land on

which St. Francis of Assisi Church, the friary, and school would be built was part of a “grant by the

Mexican Government to Don Augustus Sutter, dated June 18, 1841.”

Though founded by Germans to serve German-speaking Catholics, St. Francis of Assisi was

not a “national” parish. In chartering St. Francis, Bishop Manogue made at least two stipulations:

- Funds were not to be solicited outside the parish boundaries, and

- The parish was to serve all

Catholics within its boundaries. Thus, from its inception, St. Francis of Assisi Parish was envisioned

as an inclusive parish.

|

Map of the Confirmed Plat

of the New Helvetia Rancho (1859),

A. W. von Schmidt, Surveyor,

Lot No. 1. 8,869.64 acres [CSA] |

|

PHOtO/GRAPHICS CREDITS

Centennial logo: Judy Wegener.

Print, St. Francis Church: Dennis Rietz, S.F.O., 1995.

Postcard, Sutter’s Fort/St. Francis of Assisi Church: Sacramento Public

Library/Sacramento Room.

Photograph, Aerial view of Sutter’s Fort, St. Francis of Assisi Church:

Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection Center.

Print, St. Francis Church: Dennis Rietz, S.F.O., 1995.

World Map, 38th parallel: California State University Sacramento, Ryan Arndt,

Information Technology Consultant.

Photograph, Sutter’s Fort ruins: Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection

Center.

Map, Prince Rupert’s Land: Encarta.

Photograph, Mission San Diego: Wikipedia, Mission San Diego de Alcala.

Interactive map, Twenty-one Franciscan missions: http://missions.bgmm.com.

"Map of Russian America": courtesy of Fort Ross State Historic Park Photo

Archives, print from the Nicholas I. Rokitiansky Collection.

Photograph, Sea otters: http://www.fortrossstatepark.org

Map, Fort Clatsop/Astoria: Encarta.

Sketch, Solano Mission and Sonoma Presidio: http://www.parks.sonoma.net.

Map, Jedediah Smith: Adapted from "The Californios versus Jedediah Smith

1826–1827, A New Cache of Documents", by David J. Weber, Arthur H. Clark,

1990.

Map, Jedediah Smith in California: Adapted from "The Californios versus

Jedediah Smith 1826–1827: A New Cache of Documents", by David J. Weber,

Arthur H. Clark, 1990.

Book cover, "John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier", Albert L.

Hurtado, Oklahoma University Press, 2006.

Map, Sutter’s journey from Burgdorf, Switzerland, to St. Louis, Missouri:

California State University, Sacramento. His two round trip ventures to Santa Fe,

added more than 4,000 miles to his travels.

Map, Sutter’s journey from St. Louis to Fort Vancouver: California State

University, Sacramento.

Map, Sutter’s journey from Fort Vancouver to Honolulu to Sitka to Monterey:

California State University, Sacramento.

Portrait, John A. Sutter, Wm. S. Jewett portrait, 1853: California State

Library/California Room.

Map, Sutter’s Claims and Final Grant: "John Sutter: A Life on the North American

Frontier", Albert L. Hurtado, Oklahoma University Press, 2006, p. 64.

Map, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1848: Encarta.

Book cover, Holliday, J. S., "The World Rushed In: The California Gold Rush

Experience", Simon and Schuster, paperback cover, 1981/1989.

Lithograph, Sacramento City, 1855: Sacramento Archives and Museum

Collection Center.

Map, Sacramento River Watershed: Sacramento River Watershed Program, http://www.sacriver.org.

Book cover, "Battling the Inland Sea: American Political Culture, Public Policy, &

the Sacramento Valley, 1850–1986 by Robert Kelley". © 1989 Regents of the

University of California. Published by the University of California Press.

Diagram, Fire damage, 1852: Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection

Center.

California State Seal: California State Archives.

Map, Mt. Diablo: Mount Diablo Surveyors Historical Society, www.mdshs.org.

Photograph, Capitol construction, c 1873: Sacramento Public

Library/Sacramento Room.

Fr. Peter Anderson: Diocese of Sacramento.

Photograph, St. Rose of Lima, early 1860s: Sacramento Archives and Museum

Collection Center.

Photograph, Photo St. Rose of Lima, after 1860s: Sacramento Archives and

Museum Collection Center.

Postcard, Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament: Sacramento Public

Library/Sacramento Room.

Map, New Helvetia Rancho, 1859; A. W. von Schmidt, Surveyor, Lot No. 1.

8,869.64 acres: California State Archives.

Author photograph: Nick Situ, Ace Photo.

|

REFERENCES/RESOURCES

Baggellmann, Ted, and Thompson, Willard. “John Sutter’s Journey: 1834-1839.” Sacramento County Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 33, No.3, Fall 1987.

Bolles, Bonita L. “The Advent of Malaria in California and Oregon in the 1830.”

Sacramento County Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 36, No.4, Winter 1990.

“The Boundary Lines of St. Francis Parish: Sacramento, California.” Santa Barbara,

California: Mission Santa Barbara Archives, untitled chronicle entry, October 27,

1894.

Breault, Fr. William, S.J. John A. Sutter in Hawaii and California 1838–1839. Landmark Enterprises, 1998.

Doyle, Eleanor. “Catholic Churches” in “Our Pioneer Churches.” Sacramento County

Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 11, No.1, 1965: 5-9.

“Fort Ross State Historic Park: Russian Colony.” http://www.fortrossstatepark.org.

Heavenston, J.S. The World Rushed in: The California Gold Rush Experience: An

Eyewitness Account of a Nation Heading West. New York: Simon and Schuster,

1983.

Hurtado, Albert L. Indian Survival on the California Frontier. Yale Western Americana

Series: 35. Yale University Press, 1988.

Hurtado, Albert L. John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier. Norman,

Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

Note: Albert L. Hurtado is Travis Chair in Modern American History at the

University of Oklahoma. He is a native Sacramentan and graduate of CSU

Sacramento. He kindly responded to numerous emails regarding John

Sutter’s life and Jedediah Smith’s travels.

Itogawa, Eugene. “New Channels for the American River.” Sacramento County

Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 17, No.3, 1971.

Kelley, Robert. Battling the Inland Sea: Floods, Public Policy and the Sacramento Valley.

Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1989.

“Miasma in Sacramento: ‘A Gross and Palpable Danger.” Sacramento County Historical

Society, Golden Notes Vol. 24, No.3, 1978.

Momboisse, Raymond M., editor. “Sacramento’s Early Churches.” Sacramento County

Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 11, No.1, January 1965.

Morgan, Dale L. Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the American West. Lincoln,

Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1964.

Ogden, Adele. The California Sea Otter Trade, 1784-1848. Berkeley, California:

University of California Press, 1941.

Outpost of an Empire: Fort Ross: The Russian Colony in California. Jenner, California:

Fort Ross Interpretive Association, 1992.

Pettey, John W. “The Mount Diablo Initial Point: Its History and Use.” Spring 1988. http//www.mdia.org.

Pisani, Donald J. Merrick Chair of Western American History, University of Oklahoma

(and a native Sacramentan). Conversation with the author, SAMCC, June 27,

2008.

“The Sacramento River Watershed.” The Sacramento River Watershed Program, http://www.sacriver.org.

“Sea Otters.” http://www.fortrossstatepark.org.

Sutter’s Fort State Historic Park. California State Parks, 1989.

Weber, David J. The Californios versus Jedediah Smith, 1826-1827: A New Cache of

Documents. Western Documentation Series. Arthur H. Clark Company (Imprint of

University of Oklahoma Press), 1990.

West, Irma. “Cholera and Other Plagues of the Gold Rush.” Sacramento County

Historical Society, Golden Notes Vol. 46, No.1, 2000.

Wheeler, Mary E. “Empires in Conflict: The ‘Bostonians’ and the Russian-American

Company.” The Pacific Historical Review Vol. 40, No.4, Nov. 1971, 419-441.

Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jedediah_Smith. |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

St. Francis of Assisi Parish

| |

- Fr. Anthony Garibaldi, Pastor

- Fran Anderson, Administrative Assistant

- Cathy Flores, webmistress

- Susan Silva, volunteer editorial reader

- Rose Cartmill Joss, volunteer initial historical research

- David Sundquist, volunteer historical research Santa Barbara Mission Archives

|

California State University Sacramento

| |

- Professor Christopher Castaneda

- Ryan Arndt, Information Technology Consultant

- Khoa Van Do, Classroom Computer Lab Services Consultant

- Shawn Sumner, Information Technology Consultant

- Professor George Craft

|

Sacramento Public Library, Sacramento Room

| |

- Clare Ellis

- James Scott

- Tom Tolley

|

Sacramento Archives & Museum Collection Center [SAMCC]

| |

- Pat Johnson

- Carson Hendricks

|

Diocese of Sacramento

| |

- Rev. William Breault, S. J., Diocesan Historian and

Archives Director

|

California State Archives

Historian

| |

- Professor Albert L. Hurtado

|

Technical Support

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Long-time member of St. Francis of Assisi Parish and professional historian, Gregg Campbell (b 6/17/1935; d. 11/28/2015) wrote this history of St. Francis and its surrounding community for the 2008 Centennial of our church building. |

©

St. Francis of Assisi Parish, Sacramento, CA

|